为什么经济消化石油上涨的作用相当有限

2007-11-22

[2007.11.17] Shock treatment

Economics focus

Shock treatment震后处理

Nov 15th 2007

From The Economist print edition

Why the economy has absorbed high oil prices fairly easily, and why it may no longer

为什么经济消化石油上涨的作用相当容易,为什么以后好景不再

OIL prices have a special place in economic folklore. The two nastiest global recessions of recent decades were preceded by huge and sudden rises in the price of oil, first in 1973 and then in 1979. These twin spikes, both engineered by the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries limiting its oil shipments, are still the textbook example of an economic “shock”—a sudden change in business conditions. Abrupt increases in the oil price have prompted anxiety about stunted growth ever since.

石油价格在经济中占有特殊地位。最近几十年来,最厉害的两次世界经济衰退都是以石油价格突升而引起的,一次是在1973年,另一次是在1979年。这两次石油价格突升都是起因于石油输出国组织限制其石油生产,现在都成为教科书中实例,讲述经济“地震”,即商业状况突然改变。从那时以来,油价突升都会引起人们对经济增长下降的担心。

Higher oil prices hurt the economy because they act like a tax increase. Firms that use oil face higher costs which, if they cannot be passed on in higher prices, might mean that some production becomes unprofitable. Consumers paying more for their petrol and heating oil have less to spend on other things. If they look for higher wages to compensate for a drop in purchasing power, that will only lead to job losses.

高价的石油会影响经济,这是因为其作用就像是增加税务一样。那些使用石油的公司成本会增高,而如果他们不能通过提高销售价格将其转出,则意味着有些生产会成为赔钱生意。消费者要为汽油及燃油付出更多,而这会减少他们在其他方面的消费。如果他们想多挣些钱,以弥补购买力下降的影响,这就会导致失业。

Oil-producing countries benefit from higher crude prices so the impact on global demand depends how their extra income is spent. But even if oil windfalls are spent largely on goods produced by oil importers, the abrupt shift in the distribution of global income will still be destabilising.

石油生产国会从高价石油获益,而他们如何花费这些钱也影响着整个世界的需求。即便他们用这摇钱树上多出的钱都用来购买石油进口国的货物,世界收入分布的突然变化也依然会造成不安。

Given the gloomy history, the lingering unease about higher oil prices is understandable. A demonstration of this came on November 13th when, after a rough few days, stockmarkets rose on news that the oil price had fallen below $93. After all the talk of breaking the three-figure barrier, a drop towards a mere $90 spurred a relief rally.

回顾这灰暗的历史,人们就会理解长久以来油价升高时所产生的不安了。11月13日这种情况又展示了一次。油价掉下93美金,股市在连跌数天后应声而起。在很多人讲油价会超过百元时,油价跌到接近90美金就让股市松了口气。

Yet for all that, something has changed. Today's oil prices would have been unthinkable until very recently. Six years ago, when a barrel of crude could be bought for as little as $20, oil prices at today's levels would have raised fears of deep recession. Notwithstanding the spectre of past oil shocks, crude prices have risen to ever-dizzier heights without derailing a five-year period of strong global growth. But why has the oil bogeyman become less scary? Two new papers* by three well-known economists set out to explain. They come to similar conclusions: oil shocks do not hurt as much because oil is used less intensively than before, because the economy is more flexible and because central banks are better at controlling inflation.

尽管如此,有些情况已经改变了。前一段时间人们都没有想过当前的油价会这么高。六年前,每桶原油价格仅为20美金,当前的价格在那时会使人们担心发生经济萧条。尽管过去石油震荡的阴魂仍然在游荡,原油价格仍然达到使人眼晕的高价,并且没有阻止5年的世界经济快速增长。但是为什么这石油幽灵变得不那么可怕了呢?两份由著名经济学家写的论文解释了个中原由。他们得出了相似的结论:由于石油使用不像过去那样集中,经济更加灵活,各个中央银行均很好的控制了通胀,所以油价震荡的伤害没有以前的大了。

What makes oil special is that it is a uniquely dense and portable form of energy. It is not easy to switch to alternatives very quickly, so disruptions to supply are damaging. Yet improvements in energy efficiency mean dependence on oil is not what it once was. Rich countries use less than half as much oil as they did in 1970 for each inflation-adjusted dollar of GDP. So although prices in real terms have returned to levels last seen in the 1970s, their impact is not as powerful when set against the diminished economic importance of oil (see charts).

石油是一种密度大,便于携带的能源。换成其他能源要加以时日,所以石油供应间断会造成伤害。由于能源效率的提高,目前对石油的依赖性没有以前大了。由通胀调整后的以美金计算GDP中,富裕国家所使用的石油还不到1970年代的一半。所以,虽然石油实际价格已经回到1970年代的水平,但是考虑到经济中不断下降的石油重要性,这种影响就没有那么大了。

The blow from dearer oil is less powerful than it was and compared with their rigid state in the 1970s, today's more flexible economies are better able to take a punch. Higher oil prices have some unavoidable direct consequences on companies' production costs and on prices paid by consumers for oil-derived products. Wider damage to jobs and output depends on how well these increased costs are absorbed. If workers insist on higher cash wages to maintain their spending power, firms' costs will take an additional hit, resulting in lay-offs, higher unemployment and depressed demand. To the extent that workers take it on the chin, accepting higher oil prices as a temporary tax increase that lowers their real take-home pay, the collateral damage will be smaller. The rigidity of the 1970s economies, where union power and indexed contracts meant wages were unyielding, only magnified the adverse effects of oil shocks. Today's flexible jobs markets allow oil shocks to be absorbed less harmfully.

与1970年代时昂贵的石油相比较,目前的高价石油对经济的影响要小得多,目前更灵活的经济能够更好的对付价格上涨。对于公司生产费用及那些与石油有关的产品价格来讲,高价石油有些不可避免的直接影响。就业及产出损失的影响范围依赖于如何吸收这些费用增长。如果工人为了维持消费能力,要求增加工资的话,公司的生产费用将进一步受到影响,这将导致解雇工人,高失业率,这会进一步减少需求。如果工人的忍受能力较好,接受高价石油起的短期税收增加,减少他们的实际收到的工资的话,经济的总体损失会相对小些。1970年代的经济没有目前这么灵活,那时有工会力量,及那些与通胀相联系的合同,这意味着工资上缺少灵活性,而这些则增大了石油震荡的负面作用。而目前灵活的就业市场能够吸收石油价格震荡的影响,使其伤害没有原来大。

If consumers are more forgiving of oil shocks, it is partly because they have become more accustomed to volatile prices and partly because they have greater trust in policymakers to keep inflation under control. Dearer oil has pushed up consumer prices, but expectations of future price increases have remained remarkably stable. That in turn reflects a belief that central banks will act where necessary to keep a lid on inflation. There is a self-fulfilling aspect to that faith. Employees are less pushy in seeking inflationary wage deals and firms think twice about raising their own prices. As a result, central banks do not need to respond as aggressively as in the past to the inflation caused by higher oil prices. A less jerky monetary policy makes for greater stability.

如果讲消费者容忍石油震荡,这是由于他们已经习惯于价格波动,还由于他们更相信政策制定者能够控制通胀。昂贵的石油已经增高了消费价格,但是将来价格增长的期望值仍然很稳定。这反映了相信中央银行在必要时会采取行动,控制通胀。这里有一种自我满足的信心在内。雇员对寻求通胀工资增长并不急迫,公司也在提高产品价格时考虑再三。结果,中央银行不用象过去那样,每当石油上涨就急着控制通胀。波动较小的货币政策会导致更稳定的经济。

Pump-action problems油价的问题

Both papers help tell us why oil shocks hurt much less than they used to. But that is not to say that oil prices no longer matter at all. Neither analysis takes the run-up in oil prices over the last year into account. The rise in crude prices since the summer has been rapid even by the standards of the 1970s shocks and comes at a particularly bad time for America, the world's largest oil user. Consumers are now having to absorb a flurry of punches. Falling house prices, tighter credit conditions, rising unemployment, as well as higher prices at the petrol pump, all cloud the outlook for consumer spending.

两份论文都帮助我们了解为什么石油震荡的伤害没有以前大。但是这并不意味着石油价格不再伤害经济了。两份论文中都没有讨论到去年的油价上升。即使用 1970年石油震荡的标准来讲,今夏以来油价也是突然上涨,而且对美国,这世界上最大的石油用户来讲是特别不合时宜。消费者要经受各种打击。房价下跌,信贷紧缩,失业增加,还有油价上涨,所有这些都为消费者支出罩上了阴影。

Moreover, part of the cost of absorbing past oil-price hikes has been higher consumer debt and a huge trade deficit, both of which make America's economy more vulnerable. And though the Federal Reserve's credibility has allowed it to cut interest rates in anticipation of a downturn, the persistence of oil-led inflation may yet shift expectations of future price pressures, forcing the central bank to keep monetary policy on a tighter chain. America's economy no longer has the glass chin that it had in the 1970s. But a combination of powerful blows could still have a shattering impact.

另外,过去一部分石油价格上涨的作用是由消费者负债增加及贸易赤字来吸收,而这两种方式都使得美国经济更加脆弱。虽然美国联储会有信誉,会在预计经济下滑时降息。但是,由油价导致的持续通胀可能会转移将来价格压力的期望,使得中央银行不愿将手中货币政策的砝码出手。美国经济不再像1970年代那么弱不禁风了。但是各种因素的综合作用仍然能够产生破坏性。

*“The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks: Why are the 2000s So Different From the 1970s?”, by Olivier Blanchard and Jordi Galí. Massachusetts Institute of Technology Working Paper 07-21 (August 2007).

“Who's Afraid of a Big Bad Oil Shock”, by William Nordhaus. Preliminary draft (September 2007) prepared for Brookings Panel on Economic Activity. |

2025.12.16 图文交易计划:布油开放下行 关785 人气#黄金外汇论坛

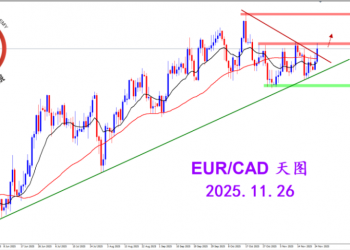

2025.12.16 图文交易计划:布油开放下行 关785 人气#黄金外汇论坛 2025.11.26 图文交易计划:欧加试探拉升 关2808 人气#黄金外汇论坛

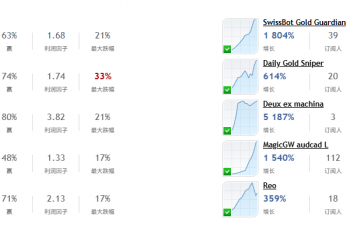

2025.11.26 图文交易计划:欧加试探拉升 关2808 人气#黄金外汇论坛 MQL5全球十大量化排行榜2900 人气#黄金外汇论坛

MQL5全球十大量化排行榜2900 人气#黄金外汇论坛 【认知】5700 人气#黄金外汇论坛

【认知】5700 人气#黄金外汇论坛